|

<Back to Field Trips and Short Courses

PRE-CONVENTION FIELD TRIP

Sedimentology, Sequence Stratigraphy and Paleontology of a Pennsylvanian Transgressive Sequence, Catoosa, Oklahoma

&

Geology of Redbud Nature Preserve

Whitney Landress, John McLeod & Doug Jordan

AAPG Midcontinent 2021

Sunday, October 3rd

COURSE DESCRIPTION:

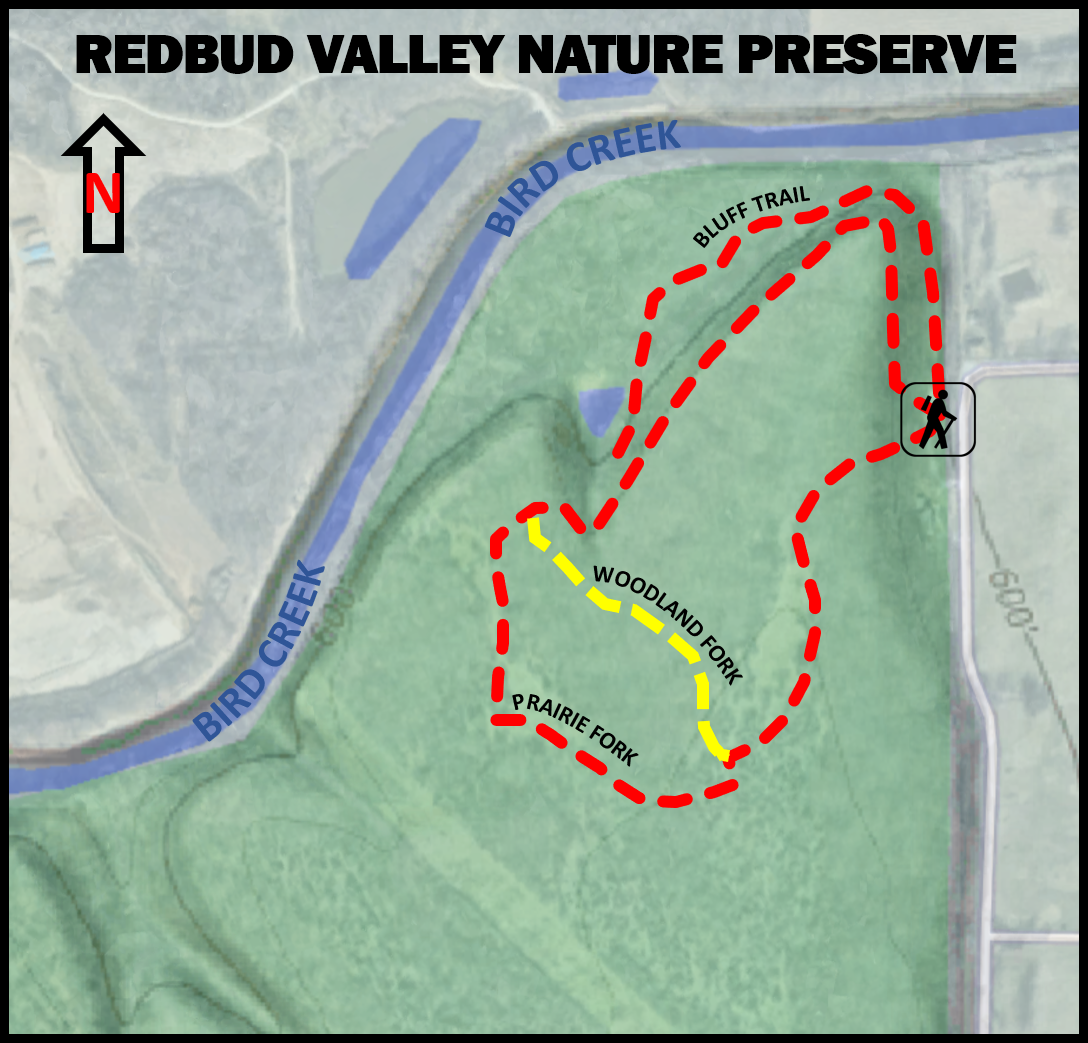

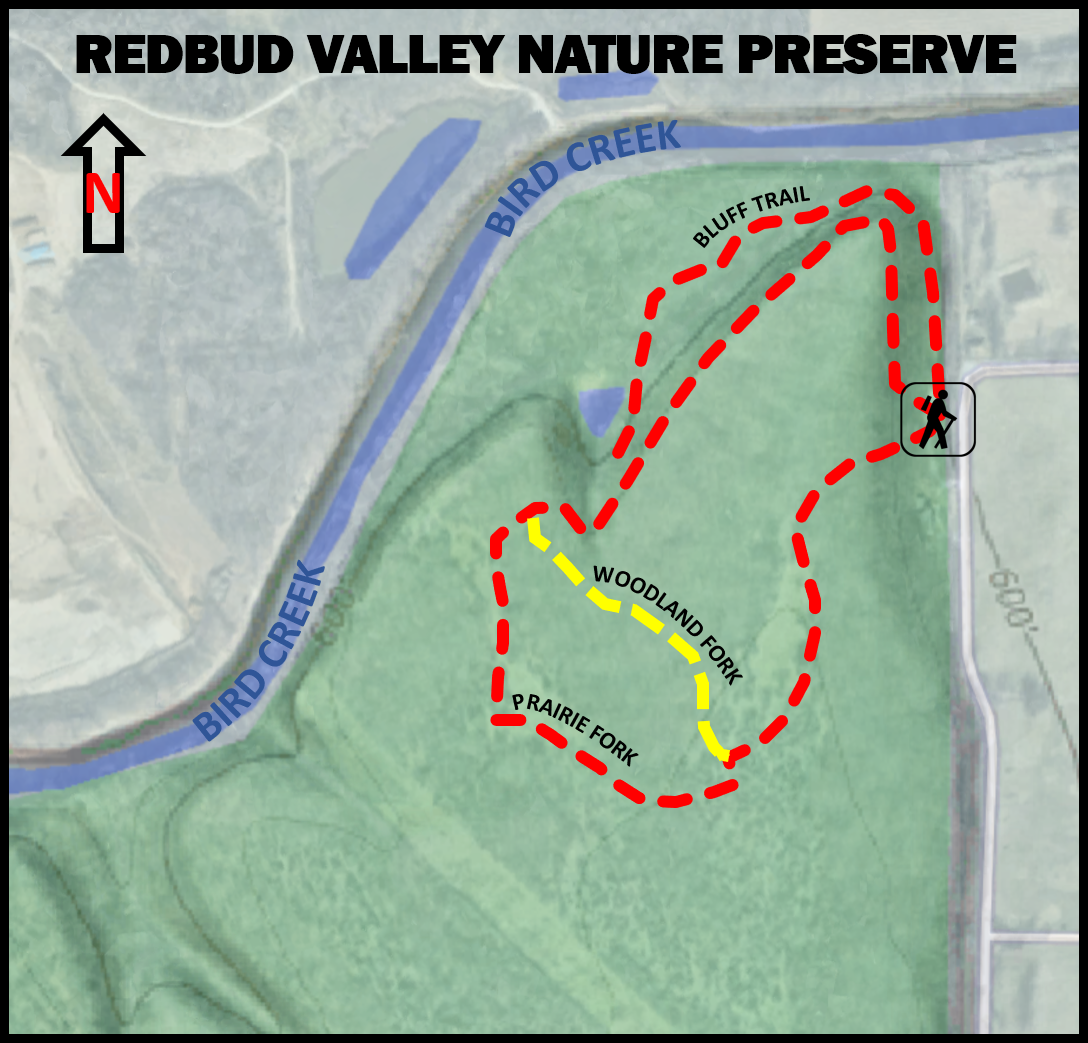

Part I: Geology of Redbud Nature Preserve

Due to the underlying rocks, and the way water flows over, around, and through them, there are a great variety of habitats in a very small area. The one-mile trail wanders through places that resemble the flat, dry, sunny upland prairies and forests of central Oklahoma's Cross Timbers. It also climbs through a shady, damp, steep-sided valley that would be at home in the Ozark Mountains. Tarantulas and cactus live less than half a mile from salamanders and ferns! Those are only the two most extreme examples. It's like a patchwork quilt of many small ecological zones, with different amounts of sunlight, water, soil, and wind in each one.

There are geological stories everywhere at Redbud Valley Nature Preserve. You might want to print this out to take with you on your walk around the trail. You can use it as a checklist, to make sure you find it all!

- Watch for fossils of sea creatures in the rocks under your feet as you climb the steps. The Oologah Limestone, a.k.a. "Big Lime", is known for its abundance of brachiopods, crinoids, and horn corals. The rock quarry to the south is mining Big Lime, mostly to use as a component in cement production. Collecting is not permitted in the preserve, but you may pick up a brochure at the visitor center that lists several public locations where you may find fossils to take home.

- The Oologah Limestone holds together well, forming big, massive cliffs and bluffs. But water trickles through the pores of the limestone like water through the holes in a sponge. Unlike a sponge, however, the limestone is dissolved by the water, and the holes get bigger as more and more water flows through them. A visible hole in the rock is called a vug, and a bigger one is called a cave. When the ceiling of a vug or a cave collapses or dissolves, it is called a sinkhole. The trail will take you past vugs and caves. One cave is big enough to crawl into, so you may want to bring a flashlight. The cave is closed during the winter, to protect hibernating bats.

- Bird Creek on the north and Redbud Creek to the east have eroded long trenches in the Oologah Limestone and cut down into the layers of rock beneath, leaving hills on either side capped with ledges of limestone. The Oologah Limestone is strong, but has a series of cracks. Rainwater finds its way into those cracks and widens them. If the water freezes, it expands and acts like a wedge, widening the crack even more.

Eventually the edges split off in large chunks, called slump blocks. The main trail goes up among a group of slump blocks and then down again through another group. The bluff trail meanders along the lower edge of slump blocks in the process of breaking away. The blocks you see on the slopes are sliding down the hill very, very slowly. The main trail's boardwalk will take you to a bench beside a slump block that tipped onto its side as it came down.

- Underneath the limestone is the Labette Shale. Shale is impermeable, meaning water does not flow through it very well. At the point where limestone meets shale, the water that has been seeping through the limestone cannot go down through the rock anymore. If that contact point is on the side of a hill, that is where the groundwater comes out as seeps and springs. (NOTE: UNTREATED SPRINGWATER IS NOT SAFE TO DRINK.)

- Shale is much crumblier than the limestone, so water and wind eat away at it much faster. All kinds of animals find shelter in the places where the shale has eroded leaving limestone overhangs. Look for the shallow pits of antlion larvae, called "doodlebugs." (NOTE: A ROCK OVERHANG IS NOT A SAFE PLACE TO WAIT OUT A THUNDERSTORM. LIGHTNING CAN STRIKE FROM THE CEILING TO THE FLOOR OF THE OVERHANG.)

- Shale crumbles into new soil much faster than limestone. Along the upland prairie trail, the rocky soil is very thin. Below the bluffs the soil is much more abundant, but the slopes are unstable, and life there is very fragile. Most of the new soil slides down the steep slope to the flat terrace below. (PLEASE REMEMBER TO STAY ON THE TRAIL TO PROTECT THE FRAGILE ECOLOGY OF THE SLOPES.)

- The soil in the terraces along Bird Creek is growing deeper for two reasons. It is sliding down from the slopes above, and Bird Creek is bringing sand and silt from Osage and Tulsa Counties. Every flood piles another extra deep layer on top of the routine daily deposits. At one point along the main trail, at the east end of the boardwalk, you can look across Bird Creek for a good view of the steep earthen banks. You can also see soil swirling along in the brown water of Bird Creek.

- Bonus: Sometimes after a hard rain, small bits of chipped flint appear along the trail under the bluffs. The flint did not form here. It was brought to this location by people who used it to make stone tools. The tiny fragments of worked stone indicate a place someone sat to make tools, thousands of years ago. It is not hard to find reasons why a stone-age craftsperson would have carried tools and chunks of flint to this place to live and work.

Part II: Sedimentology, Sequence Stratigraphy and Paleontology of a Pennsylvanian Transgressive Sequence, Catoosa Oklahoma with John McLeod & Doug Jordan

A large roadcut in near Catoosa, Oklahoma exhibits a classic deepening transgressive sequence of Cherokee Platform shallow to deep water shelf facies. The basal silty units of the Labette formation, finely laminated and dramatically deformed, grade upward into a coarser reservoir sandstone (Peru Sand) and algal limestone before culminating is black source rock shale with phosphatic nodules. The overlying massive Oologah Limestone is the major commercial source of limestone for Tulsa and is quarried extensively just west of this cut. Each facies in this sequence contains a diagnostic assemblage of plant, trace or shelly fossils

Cost: $110

John McLeod Bio

Doug Jordan Bio

<Back to Field Trips and Short Courses

|